Every few years, the Nation’s Report Card — officially the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) — provides a sobering look at how American students are performing. The most recent results released in 2024 made headlines for all the wrong reasons: 12th-graders’ reading and math scores dropped compared to 2019, with more students testing at “below basic” levels than at any point in recent memory. 8th-grade science scores also fell, widening gaps for students who were already struggling.

These results matter far beyond test scores. For many students, 12th grade is the final checkpoint before graduation and entry into college or the workforce. If graduates leave high school unable to read or compute at a basic level, the ripple effects touch college readiness, employability, and long-term equity. Districts that already struggle to prepare students for life after high school now face even greater challenges.

This blog delves into the story behind the NAEP results, examining what the assessments reveal, the changes in instruction that occurred during and after the pandemic, and why simply blaming digital learning doesn’t capture the whole picture. Most importantly, it examines what research reveals about high-dosage tutoring, when conducted with quality and consistency, as one of the most effective levers for reversing declines.

What the NAEP Results Tell Us

The 2024 NAEP reports painted a bleak picture across subjects and grade levels.

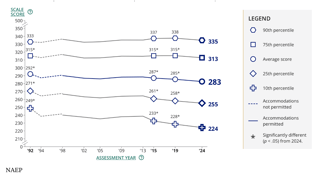

- 12th-Grade Reading & Math: Compared with 2019, both subjects saw declines. The proportion of students scoring “below basic” — the lowest achievement category — rose sharply. Math scores, in particular, reached their lowest point since NAEP began tracking 12th-grade performance in the 1990s.

- 8th-Grade Science: Achievement dropped, and more students fell into the “below basic” range. This decline is particularly concerning as science is increasingly tied to workforce readiness in STEM fields.

- Widening Gaps: Students at the bottom of the performance distribution fell further behind, while higher-achieving students held steadier. The result is a widening chasm between top and bottom performers.

- Historical Context: Reading scores have been sliding for decades, but the most recent data shows the sharpest drop in years. In math, what once looked like steady progress has not only stalled but reversed.

These declines didn’t happen in a vacuum. A recent K-12 Dive analysis noted that the drops in math achievement come on top of long-standing challenges, including persistent teacher shortages, ongoing debates over curriculum (“math wars”), and reform efforts that haven’t yet translated into measurable gains. The pandemic disrupted instruction in unprecedented ways, but the cracks in the foundation were already visible.

For policymakers and educators, these findings serve as a wake-up call. Without meaningful intervention, schools risk graduating more students who lack the literacy and numeracy skills essential for college, careers, and civic participation.

Assessment & Instruction Before, During, and After the Pandemic

To understand today’s results, it is helpful to examine how assessment and instruction have evolved.

- Pre-pandemic: Students faced rising accountability measures, but many districts struggled with the implementation fidelity. Achievement gaps were already significant.

- During the pandemic: Instruction shifted online almost overnight. Students faced inconsistent internet access, inadequate devices, and limited support from adults. Teachers had to redesign curricula with little training. Engagement plummeted, particularly for low-income students.

- After the pandemic: Districts experimented with hybrid and recovery programs. Some students had summer or after-school learning opportunities, but implementation varied widely. Many never received the sustained support they needed.

Why Blaming Digital Alone is Too Simple

It is tempting to attribute the declines to Zoom fatigue, missing devices, or lack of internet access. Those were real barriers. However, research reveals that the story is more complex.

Digital learning exacerbated inequities where resources were scarce. Students in households with limited connectivity or without adults able to support at-home learning were hit hardest. Engagement also dipped when teachers, often underprepared for remote instruction, struggled to adapt lessons.

But digital tools are not inherently harmful. Studies have shown that other countries effectively leveraged technology during school closures. Even in the U.S., districts with robust support structures and aligned instructional practices saw students fare better. The real issue was not the medium, but the quality and consistency of its use.

This lesson applies equally to interventions like tutoring: it’s not just whether you do it, but how you do it that determines success.

What the Data Says About Tutoring / High-Impact Interventions

Well before the pandemic, research consistently showed that high-dosage tutoring can yield learning gains equivalent to an additional year of instruction when delivered with fidelity. Studies cited by EdResearch for Recovery and others indicate that three or more sessions per week, structured curricula, and strong tutor-student relationships are key factors in driving success.

Following the pandemic, districts nationwide launched tutoring programs with federal relief funds. The results, however, have been mixed.

Many programs provided only one session per week or less, far below the dosage shown to be effective. In some cases, logistical constraints meant that students received just a handful of sessions throughout the entire year.

The consequence: students often gained only one or two months of extra learning in math or reading. On a per-minute basis, tutoring was still highly effective. But the total number of minutes students actually received was far below research benchmarks.

What "Doing It Right" Looks Like: Features of Effective High-Dosage Tutoring

The good news is that research also gives us a clear picture of what works:

- High Frequency and Sufficient Time: Tutoring should occur at least three times per week and accumulate enough total hours to close gaps effectively.

- Small Groups or 1:1: Ratios of four students or fewer are optimal.

- Trained Tutors and Consistent Materials: Tutors should utilize aligned curricula and receive training, rather than relying on ad-hoc lesson planning.

- Backward Remediation: Students must be allowed to revisit earlier skills while still accessing grade-level content.

- Monitoring and Adjustment: Programs must track attendance, engagement, and progress to ensure fidelity.

The September 24 literacy article highlights the delicate balance: students with learning disabilities require both exposure to grade-level content and opportunities to develop foundational skills. Ignoring either side shortchanges students. This is precisely why tutoring must be flexible; able to meet students where they are while steadily lifting them to grade-level standards.

Why Target Middle and High Schools & What Missing Backward Remediation Means

Much of the public conversation has focused on elementary students, but the NAEP results make clear that high school deserves urgent attention. 12th-graders are entering the workforce or higher education with record-low math and reading scores.

The danger lies in pushing students through grade-level material without ensuring they have mastered the basics. A high school junior struggling with algebra may, in fact, need support with 8th-grade fractions. Tutoring that allows for targeted backward remediation builds confidence and fills gaps that would otherwise persist into adulthood.

As the literacy article highlights, this balance is particularly critical for students with learning disabilities, who require tailored support to access both foundational and grade-level content.

Policy / School / Community Actions that Should Be Taken Now

The decline in the NAEP scale demands systemic responses. Districts, states, and policymakers must:

- Prioritize High-Dosage Tutoring: Budget for it at the federal, state, and district levels, recognizing its proven impact.

- Invest in Recruitment and Training: With teacher shortages persisting, programs should creatively recruit paraprofessionals, retired educators, and vetted external providers to address this need.

- Schedule Intentionally: Build tutoring into the school day or extended-day models, rather than treating it as an optional add-on.

- Use Assessments Wisely: Diagnostics and ongoing formative assessments should guide placement and progression.

- Focus on Equity: Direct resources toward the lowest-performing students and those with disabilities, who risk being disproportionately left behind.

- Evaluate and Adjust: Track results and scale up what works, while refining or discontinuing ineffective approaches.

Special education complaints underscore the stakes: families are increasingly turning to formal disputes when students with disabilities are not adequately supported. Proactive investment in interventions like tutoring can prevent these failures before they escalate.

Possible Objects / Counterarguments & Responses

- “It’s too expensive.”

- While high-dosage tutoring requires investment, the long-term costs of underprepared graduates — in remediation, lost productivity, and social services — are far higher. Districts can also explore phased rollouts or cost-sharing partnerships.

- “We don’t have enough staff.”

- Creative recruitment strategies, coupled with remote tutoring options, have helped districts overcome staffing shortages. The key is quality oversight, not abandoning the model altogether.

- “Students won’t want to ‘go backwards.’”

- Framing remediation as growth and progress, rather than punishment, helps reduce the stigma associated with it. Programs that foster relationships and celebrate incremental progress tend to see higher engagement.

- “Can’t AI fill this gap?”

- Emerging technologies, such as AI companions, may support student well-being, but as K-12 Dive reported, they are no substitute for trained educators. Tutoring succeeds not only because of instructional precision but also because of the relational trust between student and tutor.

Conclusion

The latest NAEP results are not just a data point. They are a warning sign that too many students are leaving high school without the skills they need for life after graduation. The pandemic exacerbated existing inequities, but structural challenges, including teacher shortages and curriculum debates, remain unresolved.

Blaming digital learning alone is too simplistic. The solution lies in implementation: doing what we know works, and doing it well. High-dosage tutoring, when delivered consistently and with fidelity, is one of the most powerful tools available to schools today.

The urgency could not be greater. Students cannot afford another decade of stalled or declining scores. Districts, states, and policymakers must act now to invest in proven interventions, ensure equity of access, and support both students and educators in closing the gaps.

The hopeful note is this: the research exists, the models exist, and the capacity exists. What’s needed now is the will to prioritize what works and to give every student, regardless of background, the chance to succeed.